22 November 2023

Three years of UK aid cuts: Where has ODA been hit the hardest?

This guest blog was written by Development Initiatives’ Paul Wozniak, based on a recent factsheet. You can read more resources about aid on the DI website.

Following a consistent decline in UK official development assistance (ODA) over the past three years, this blog highlights that…

- in-donor refugee costs have roughly tripled since 2021

- the sharp rise in refugee costs was driven primarily by high initial accommodation costs (followed by Ukraine-specific projects)

- high refugee costs are diverting aid from other sectors and the countries experiencing the worst poverty.

… and considers what’s next for UK aid.

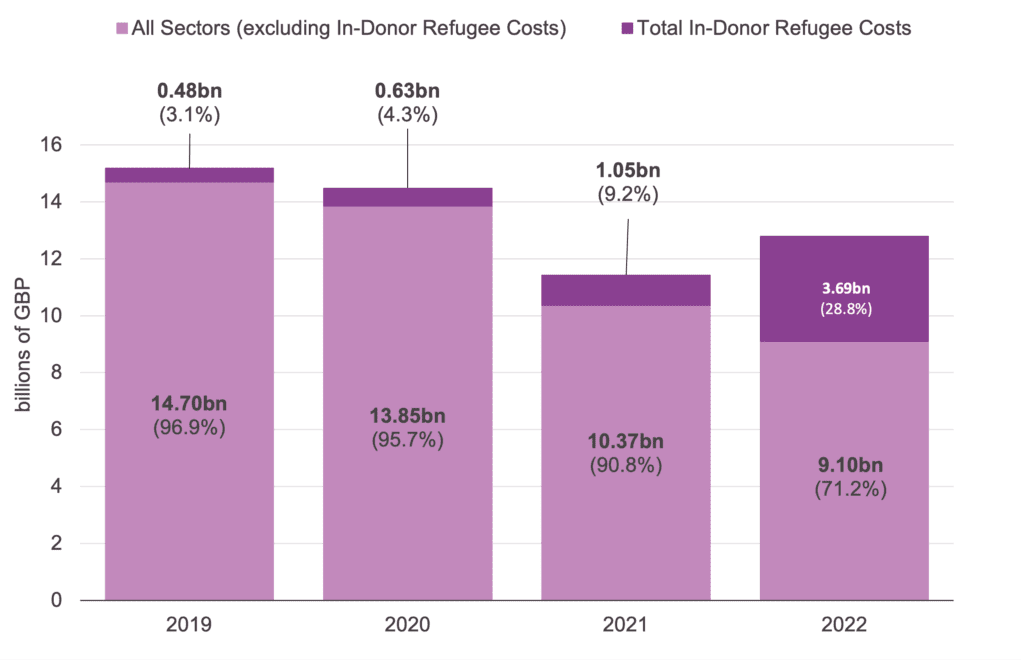

In-donor refugee costs have roughly tripled since 2021

With the recent FCDO White Paper signalling a change in the direction of UK ODA, it is useful to examine recent trends in aid to see which updates might make the most impact. The latest Statistics on International Development paper has provided a final overview of the UK’s ODA spend in 2022. (ODA, commonly known as aid, is the spending reported to the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the OECD.) The report revealed an increase in total ODA from £11.4 billion in 2021 to £12.8 billion in 2022, slightly increasing the ODA–GNI ratio from 0.5% to 0.51%. Closer examination reveals that the bulk of this change is due to in-donor refugee costs, which have jumped by roughly threefold since 2021, from £1.05 billion to £3.69 billion. When discounting these flows towards refugee costs, the UK’s total ODA actually decreased.

Figure 1: Aside from in-donor refugee costs, all other sectors decreased relative to 2021

UK’s in-donor refugee costs and total ODA, 2019–2022

Source: Development Initiatives based on Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) data, September 2023.

Notes: ODA = official development assistance.

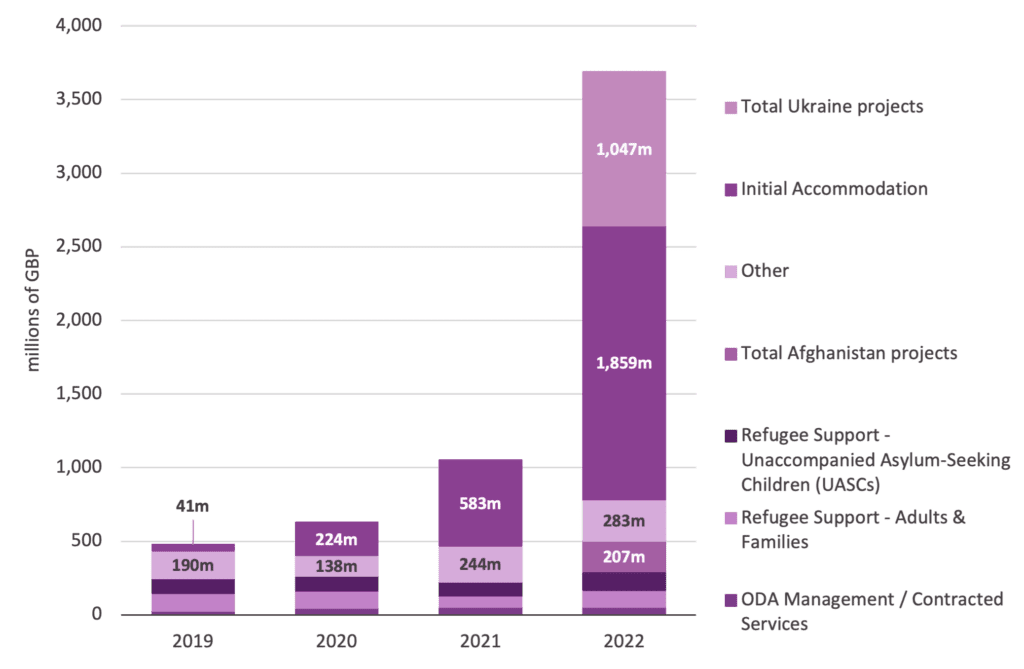

The sharp rise in refugee costs was driven primarily by high initial accommodation costs, followed by Ukraine-specific projects.

In-donor refugee costs are evidently the largest recipient category of UK international aid in 2022, measuring at 29% of overall ODA. The Statistics on International Development report cites the increase as being driven by higher accommodation costs, as well as by Ukraine temporary protection visa schemes. In 2022, Ukraine-specific projects were allocated 28% of in-donor refugee costs. While this is a significant share, these projects do not fully explain overall increase. Even excluding Ukraine-specific projects, UK in-donor refugee costs still more than doubled between 2021 and 2022. The most significant spend was on initial accommodation for asylum seekers, which accounted for £1.86 billion in 2022 – 50% of all in-donor refugee costs. This was an increase of roughly 220% from 2021 (when it was already unprecedently high) and was dispersed primarily on hotels temporarily housing asylum seekers.

Figure 2: The sharp rise in refugee costs was driven by increases in initial accommodation and Ukraine-related financing needs

Breakdown of UK ODA in-donor refugee costs, 2019–2022

Source: Development Initiatives based on Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) data, September 2023.

Notes: ODA = official development assistance. Total Ukraine projects includes all in-donor refugee costs with the word ‘Ukraine’ in the project title and consists of flows under the following project titles as listed the FCDO: child benefit assistance for Ukraine refugees fleeing conflict in Ukraine, Homes for Ukraine, Homes for Ukraine – education funding (22–23 FY), Homes for Ukraine scheme, Ukraine extension scheme, Ukraine families visa scheme, Ukraine Family Scheme, Ukraine Extension Scheme, Homes for Ukraine Scheme. Total Afghanistan projects consists of flows under the project titles as listed by the FCDO: Afghan citizens resettlement scheme (ACRS), Afghan resettlement scheme – ACRS element, Afghanistan citizens healthcare costs in bridging accommodation and child benefit assistance for Afghan refugees fleeing conflict in Afghanistan. ‘Other’ consists of remaining project titles under refugees in donor countries (broad sector code 930).

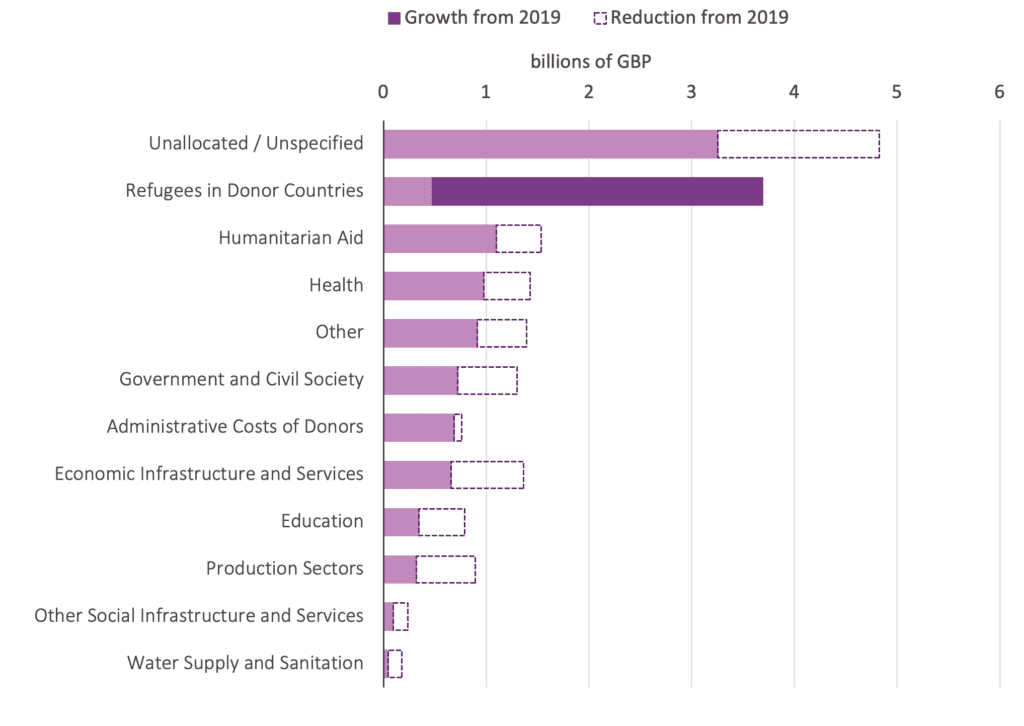

Under a squeezed ODA budget, high refugee costs are diverting aid from other sectors and countries experiencing the worst poverty

While refugee costs have increased since 2019, UK aid has declined to all other sectors. As outlined in another DI blog earlier this year, the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) spending on asylum seekers lacks accountability, leaving room for inefficient ODA allocations. As in-donor refugee costs are counted as ODA, the Home Office has little incentive to try to control and allocate costs efficiently, as they will not affect any of its programmes. As stated by the ICAI, refugee costs are absorbing a greater share of a shrinking aid budget, resulting in the FCDO being forced to reduce aid towards other sectors, including those in countries experiencing extreme poverty.

Since 2019, categories such as Education and Water supply and sanitation have arguably been impacted the most, decreasing by 56% and 74% respectively since 2019. Health has also seen a large decrease, falling by 32% – when excluding allocations towards Covid-19 control, that figure is even lower, measuring at 48%. To put in perspective the imbalance of UK ODA sectors, in-donor refugee costs over the same time have seen a rise of 673%.

Figure 3: In-donor refugee costs are the only subset of UK ODA to have increased since 2019

Changes in volume of UK ODA by sector, 2019–2022

Source: Development Initiatives based on Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) data, September 2023.

Notes: ODA = official development assistance.

Under an already tightened aid budget of 0.5% of GNI, in-donor refugee costs are decreasing the share of aid allocations towards those who need it the most. While 2022 saw the greatest volume of refugee spending yet, it is possible that these costs have peaked. It is likely that in-donor refugee costs will fall in the coming years as the number of refugees leaving Ukraine reduces, as well as the recent indications that the UK will no longer be able to count as ODA costs associated with asylum-seekers arriving via channel-crossings, following the recent legislation preventing them from obtaining refugee status. In addition, the FCDO 2022–23 annual report indicates an increase in ODA in the coming years, particularly for lower income countries. This is confirmed by the recent White Paper, stating a commitment to spend “at least 50% of all bilateral ODA” towards LDCs. This aim is part of a larger updated principle which prioritises ODA towards poverty reduction and where it is most effective. Surprisingly, the white paper made no direct mention of in-donor refugee costs, despite their increasingly large impact on UK aid over recent years. However, if in-donor refugee costs decline as seems likely, this could free up significant resources to be spent on those experiencing the greatest poverty. Despite significant drops in ODA from the FCDO in recent years, there are still reasons to remain optimistic for the future of UK aid.

To hear more from DI, sign up to our newsletter or share your thoughts with us on Twitter or LinkedIn.